20. "Tall, dark, rather handsome"

- Stephanie Brown

- Jun 29, 2020

- 6 min read

When we left Paul Gauguin in Pont-Aven--before we dropped Clovis off, and before we examined whether or not M. Gauguin could be classified as "nice,"--when we left him, he was holding forth at one of the tables outside of the Pension Gloanec. His audience was a young Englishman, Archie Hartrick. Gauguin and Hartrick were talking, or Gauguin was talking and Hartrick was listening, about drawing and illustration.

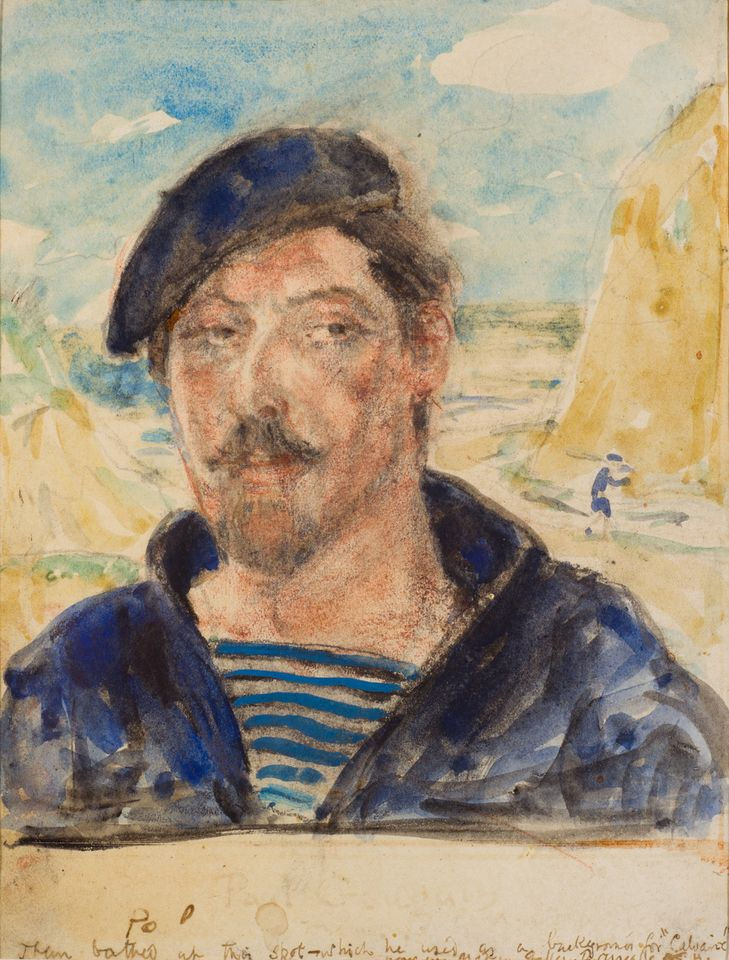

The story has evolved in the last few weeks. Earlier this month, the Courtauld Gallery in London purchased a portrait of Gauguin made by Hartrick. Here it is:

The portrait shows Gauguin from the chest up--broad shoulders, a carefully trimmed moustache and goatee, his eyebrows cocked ever so slightly. He's dressed not as a gentleman painter but as a Breton fisherman--the beret, the striped jersey, the blue pullover are the almost too-perfect costume of someone who is consciously creating an image. Gauguin is all ruddy cheekbones and insouciance.

The watercolor had been in a family collection until a few years ago, when it was consigned to the Liss Llewellyn Gallery in London. Martin Bailey, who writes regularly on the Impressionists for The Art Newspaper, delivered the news of the purchase. Bailey has been digging around in the Hartrick papers for nearly 20 years. His research suggests that Hartrick had made the portrait by 1913. It has been in a private collection since Hartrick died in 1950 and was previously only published in black and white. The watercolor is Hartrick's middle-aged memory of a man he knew in his early twenties. Did Gauguin traipse around Pont-Aven that summer dressed up as a Breton fisherman, or did Hartrick paint him thus to emphasize the location and the context? Did he want to show us that this is the sort of outfit that Gauguin would have worn? Is this how Hartrick pictured him in his mind's eye all those years later?

Bailey suggests that this portrait was meant to accompany a brief memoir of his time with Gauguin that Hartrick published in a London literary journal, The Imprint, in May 1913. The Imprint lasted for less than a year. Issues of it are rare; the copies in the British Library are not only not digitized, they are marked "unfit for use." Bailey would have been able to review the May 1913 issue only under a librarian's watchful eye. I wanted to learn more about Hartrick's written description of Gauguin because I wanted to know more of what it was like to sit on the terrace with him that summer.

Alas, I cannot spend an afternoon at the British Library. But I can find my way around Gallica, the website of the French National Library. As it happens, the Parisian journal L'Occident published translated excerpts of Hartrick's memoir in the same month as it was published in English. The reviewer and translator, François Fosca, was active in the Paris art world for decades as a critic and writer.

And so, from Fosca's translation, I learned that Hartrick described Gauguin as "reserved, circumspect, almost bitter, more like an English or Scotsman than an excitable Frenchman." He was a hard man to know: "il était difficile d'entrer dans son intimité." Hartrick's portrait in words in his essay matched his watercolor: Gauguin was “tall, dark, rather handsome, with a fine powerful figure and about forty years of age, wearing a blue jersey, and a beret

on the side of his head.” The portrait shows him in front of a crique, a cove, with a break in the headlands where it's possible to scramble down to the beach.

In his memory, the middle-aged Hartrick has posed Gauguin in front of the same setting as the painter used for his 1889 Breton Calvary (The Green Christ). The headlands have the same shape; the peasant over Gauguin's shoulder is another version of the one in the painting. He may be carrying on his shoulder an oyster rake; in 1886, and still today, the cultivation of oysters was an important part of the local economy. Workers toting rakes on their shoulders would have been a common sight along the shore.

At the bottom of Hartrick's sketch we can read a fragment of a notation: "Paul Gauguin then bathed at this spot--which he used as a background for 'Calvaire.'" Perhaps he means his choice of setting to convey authenticity: before Gauguin painted the scene, it was a favorite swimming spot.

We cannot confirm exactly when the painting was made, and how much of Gauguin's later legend went into that beret and Breton pullover. But what I think we can trust is Hartrick's note: the painters bathed at this spot. Pouldan was a swimming beach. Today, at Pouldan, you can attend sailing school. You can spend a lazy afternoon on the beach. The corniche, or coast road, de Poulhan (sometimes with an h, sometimes with a d, the spelling varies by century) runs along the headlands where the Aven river flows into the Atlantic. The walk is an hour or so from Pont-Aven, across the fields. The Pont-Aven painters covered the area from the village to the coast with their easels, brushes, stools, paints; according to one travel guide, visitors could tell they were close to Pont-Aven by the sound of the scratching of brushes on canvas.

Archie Hartrick had come to Pont-Aven to paint and to hang out with painters; he was 22, the son of a retired Captain in the British army. Hartrick began by studying painting and drawing in London and then, in early 1886, went across to Paris and enrolled at the Académie Julian. The summer exodus brought him, alongside other painters and students and student-painters, to Pont-Aven and the Pension Gloanec. In his 1913 recollections, he describes seeing Gauguin return from a day of painting with a brightly-painted canvas depicting young boys stripping off their rough linen shirts and bathing in the mill pond outside the village.

Hartrick and the other painters are sitting outside of the Pension, talking over their days' work, needling each other, jockeying for position over the first absinthe of the evening. The leader of the group--an accomplished and respected painter, whom Hartrick names with the initial V, and who others have worked out was the Dutch painter Hubert Vos--calls out Gauguin for his bright colors and splotchy, impressionistic brushwork. Vos makes some unflattering comparisons between Gauguin and Rembrandt. Did Gauguin think these scratches and splotches would replace the Night Watch? There's general laughter. Gauguin responds with a tight-lipped smile. But within a week or two, some of the younger artists are watching for Gauguin to leave in the morning and following him, setting up their easels near his and mimicking his style. Not to make fun, but to copy. And learn. And, perhaps during the hottest part of the day, to scramble down to the sea for a swim.

Hartrick's memoir and portrait starts to outline for us the look and feel of that summer in Pont-Aven. The days are long. The artists are trying to capture village life, country life. They're searching for the next big thing. Hartrick notes that Gauguin disdained art that attempted to represented three-dimensional depth on a flat surface or that tried to fool the eye of the viewer, to appear lifelike. The artists are looking over each other's shoulders, comparing notes. There's lots of painting and sketching. There's also plenty of time sitting around in front of the Pension Gloanec on the village square. There's doing the work, and then there's talking about doing the work.

Reading Hartrick's recollections, we can see Gauguin move from being on the outside of the group--mocked as he walks past with his colorful paints--to sitting at the center, holding forth on illustration and drawing. On what was wrong with all those Salon painters turning out their annual masterpieces. On how he would change all that.

It may seem that there is nothing new under the sun. And then there's a portrait that hasn't been seen before, and that portrait opens up a new path, with new vistas.

Comments